THE VILLAGE VOICE

Week of August 16 - 22, 2000

On the Road in Provincetown

Shore Leave

(link to directly to Village Voice Version of Article)

by Eileen Myles

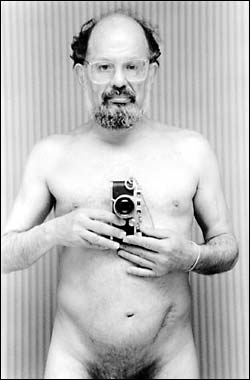

Man in the mirror: Allen Ginsberg’s 1987 Self Portrait

photo: Allen Ginsberg/courtesy of Schoolhouse Center

The general feeling in Provincetown on a Friday night is that you could

bump into someone from any part of your life. Family member, ex-lover,

someone you went to high school with—Commercial Street is a quintessentially

American street. Framed by history, Provincetown is a virtual mall, as

teeming as eBay, yet the ocean's just steps away. Even more crowded than

other resorts, P-town is on a tiny spit of land that is sorely overdeveloped

(just like New York), steadily driving out the local working class, shrinking

the public schools, converting a defunct fishing economy into a service

economy. Yet these same class conflicts are, at least for now, making

for an oddly inflected, spirited, and authentically new/old bohemian art

colony. The vehicular traffic pushes one way, heading west toward the

breakwater, the end of Cape Cod where the Pilgrims landed. But the human

traffic is pushing east, and we're going to see art.

Michael Carroll, a painter and the director of the Schoolhouse Art Center

(494 Commercial, www.schoolhousecenter.com), tells me there's a Roman

aspect to all of Provincetown's art legacy, a historical too-muchness,

like a beautiful old graveyard that keeps heaping more and more on top

of a never-quite-absent past. Schoolhouse, which is the heart and engine

of a very New York-driven art scene exploding on the Lower Cape, is unique

in that it's a for-profit gallery that also provides artists with space

to work. Of P-town, Carroll says: "It's a place to sit still and

do the same thing, wringing the same materials, shoving the same words

into position, pushing again and again. It's very obsessive here,"

he grins.

Schoolhouse opened in 1998. Its building once housed the Long Point Gallery,

which carried the ball for the old-boy network of abstract expressionism

that held the town captive aesthetically for many years. Today, Schoolhouse

is a web of nooks and hallways and exhibition spaces upstairs and down.

In the Driskel Gallery, Allen Ginsberg's nudes are seeing their first

light of . . . well, halogen. Still our first bard ("I remember when

I first got laid, H.P. graciously took my cherry, I sat on the docks of

Provincetown, age 23 . . . "), Ginsberg made photos that are a luminous

equivalent to his telegraphic verse. Begin with his own touching nude

self-portrait: He holds a black camera vertically at midsection, like

an arrow pointing to his sweet, stroke-marked mug. Then your gaze slips

down his slim torso to a vulnerable scar from gallbladder surgery. The

men and boys that inhabit the Ginsbergian myth of love range from Mark

(Ewart)—eyes shut and knee bent toward the viewer, a peaceful paw

holding his belly, graciously flocked by rumpled sheets—to a rare

seminude of the old geezer himself, Bill Burroughs, angular and resplendent

on chenille.

As you enter Schoolhouse, a single painting on the back wall of the gallery

faces the street. Doug Padgett's grand Untitled is a cartoony 19th-century

vista of drippy, cellular stalactites hanging deep within a morphing natural

interior that is oddly reminiscent of small paintings of the vaults of

Dutch churches. Two or three human witnesses stand in the lower right

and one crosses the bottom of the painting on a tourists' ramp; their

hair flickers in the same yellow, blue, and red daubs that animate the

painting's pulsating, ancient stone.

Like Padgett, who labored on his painting for a year, many of the artists

in P-town this summer are quietly confronting time in their work. Melanie

Braverman shows a single white cotton quilt behind glass further down

the same wall. It's blocked off in red stitching that says: "Love,

Death, Love, Death. . . . " The quilt is a relic from Braverman's

large Love and Death July installation, which featured a fractured poem,

written a few phrases at a time on a series of tiny open books framed

in glass, all together, an elegantly paced memorial to a friend who killed

herself in the fall. Under each phrase Braverman attached a small plaster

vessel—a tiny eyecup for tears. The minibook sections are being sold

off individually, and they are going like hotcakes. Folk art and irony

frequently meet here, perhaps as a result of the locale's physical isolation

combined with rabid tourism.

I stepped out into a twilit Commercial Street where foot traffic, scooters,

and wobbly bikes surged, filling the narrow street. On holiday weekends

it feels like the Day of the Locust. Pat de Groot has lived across from

Schoolhouse for almost 40 years, and shows at the Cherry Stone Gallery

in Wellfleet (70 East Commercial Street) as well as at Pat Hearn this

fall. Her vision is impossibly simple and bold. She works quickly with

a palette knife, making tiny Zen-like paintings of the rising and falling

line between sky and sea. The line collapses into a small, thin scumble

of blue or explodes in a fizzy spattering of yellowed white foam. On the

opposite wall at Cherry Stone, sculptor Paul Bowen specializes in shipwreck,

honing small pieces of found wood into conceptually edged constructions.

The window of the Albert Merola Gallery (424 Commercial), a smallish storefront

about five minutes from Schoolhouse, holds Duane Slick's beckoning single

hand and arm, one of a series of pearly acrylics on linen. In Merola's

back gallery, there's a selection from its stable, which includes James

Balla, Richard Baker, Donna Flax, Jack Pierson, and John Waters, with

his funny photo collages. I return loyally to one of Helen Miranda Wilson's

small oils on panel. Boxing Day is a flurry of clouds scurrying away from

an anxious but constant moon. It's silvery, moving across the viewer's

face like a quick but unforgettable vision.

Smack in the middle of the strip, but still East

End, the Bang Street Gallery (432 Commercial) is showing Jennifer Ditacchio,

the harbormaster's daughter, a local girl via Yale, whose bold striped

canvases manage to connect the ab-ex moment to a more savvy postmodern

read on landscape. There's a cocky roughness to her blue, white, and mutating

gray designs. Each of these hunky minimalist canvases (stripes, stripes,

stripes) feels as brutally uncontestable as the weather. The water that

slurps and beckons on the other side of Commercial works pretty much the

same way, cheerfully or fatally striped, whatever—no amount of thought

can override it.

Dianna Matherly's new work at Tristan (148 Commercial) trumpets light

and dark and bravery. The show mounted here last fall, "In Honor

of Survival," culled a terrific array of new and recognized talents

focusing on this theme. Several of those participating artists died this

past winter. Now Matherly presents a tributary show of mixed media. Four

oil paintings with a similar memorializing intent are funky, allegorical

takes on the disordering power of illness.

Sal Randolph is twisting thousands of yellow chenille stems (pipe cleaners)

into a cloudlike sculptural form. Her studio upstairs in Schoolhouse boasts

a computer named Bruce, reciting her poems and splaying a gorgeous array

of cascading wallpaper on its screen. "This will go in a glass case

downstairs in September," she says, pointing to the growing yellow

mass, "with rope-light snaking through." "Do you think

it needs sound?" she wonders.

"The place is weird," says Jack Pierson. "I was afraid

to come here when I was a child. I mean," he adds softly, "that's

what we like about it." Pierson is probably the best symbol of the

new/old P-town art scene: an artist who makes work that's not so much

"about" life as it is about how he imagines it. On September

1, Pierson will exhibit at the Provincetown Art Association (460 Commercial),

the longest-standing art space in town, practically a museum, which is

currently bursting with "Hans Hofmann: Four Decades in Provincetown."

"No fences, nudes, beaches," promises Pierson, referring to

practically everyone's proclivity to produce work that flies here. He's

planning to install a group of new word sculptures—his own take on

Cape Cod's dark past. "Artists almost feel trampled by the beauty

here. It's the light," says Jack, laughing.